In the preamble to my free speech series, I quoted Dave Chappelle on how Trump became president by exposing the political system’s underbelly. Trump’s ascendance, of course, was nourished by a growing iconoclasm within the modern right. Welcome to the dark side of American politics.

Conservatives believe that the media, academic institutions, and federal government have formed a syndicate indifferent to, if not actively hostile towards, the nation’s well-being. It follows that anyone speaking on the syndicate’s behalf is tainted by association. Consequently, many right-leaning dissenters retreat to conspiratorial bubbles that waft them from the mainstream, pointing to the growing divide as evidence that they were right all along.

Instead of building bridges between the establishment and its discontents, social networks ban heterodox users in the name of “misinformation” — with many victims aiding their defenestration by spreading lazy falsehoods about elections, vaccines, and child sex rings. Unfortunately, network censorship only encourages progressives to swarm the remaining hubs in an effort to drive out the wicked.

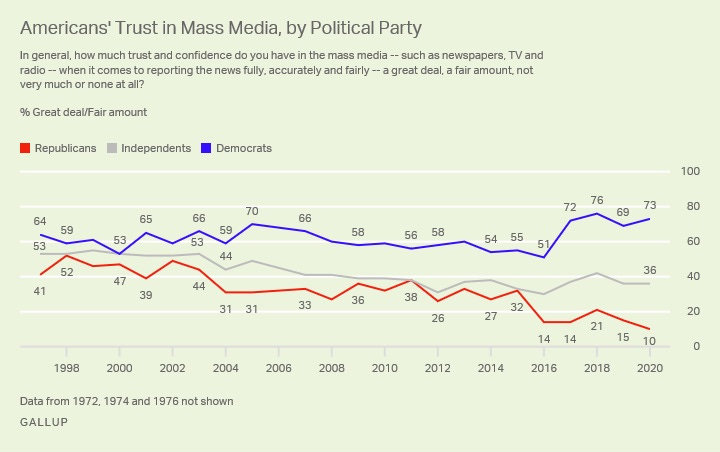

These trends have further polarized America. According to a series of Gallup polls conducted since the turn of the century, Republican trust in the fourth estate has plummeted while the Democrat’s endorsement has ascended new heights. The confidence gap between the political parties has only widened during the Trump era:

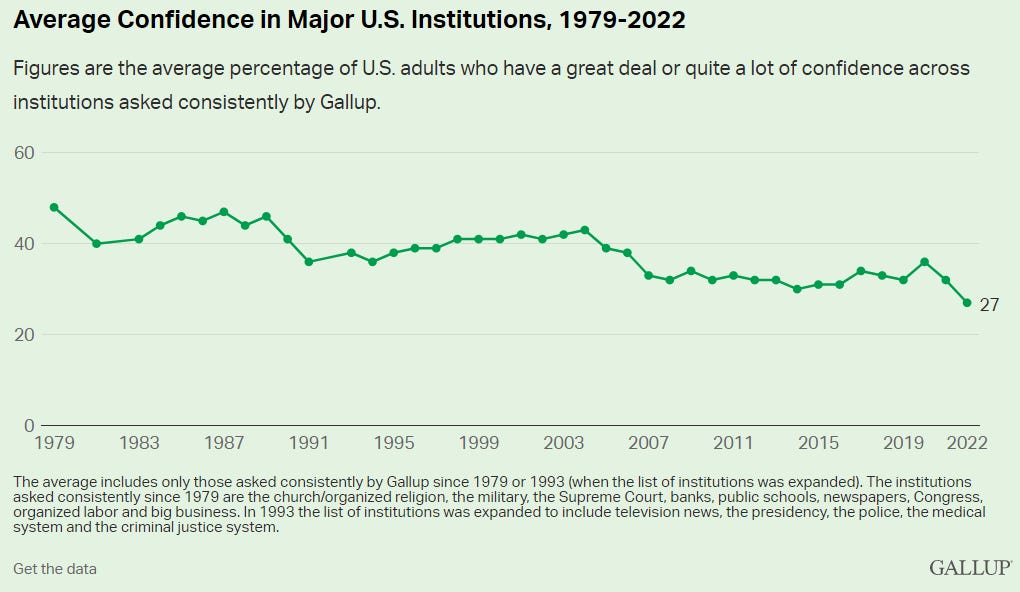

Yet these recent events are symptomatic of an older trend. The public’s faith in the government and other civic institutions has been eroding for decades:

These anti-establishment currents, which obviously predate social media, correlate with 1) the decline of religious and civic organizations, and 2) the concentration of wealth in ever-fewer hands. The rich gain power while the masses tune out.

The growing wonkocracy has also dampened public engagement. Government officials rely more than ever on a nexus of think tanks, computer models, and expert opinion for guidance, and as expert opinions converge, the range of acceptable policy options diminishes. Congress currently manages business downturns with carefully-timed stimulus packages while the Fed squeezes and relaxes the money supply to keep aggregate demand on track. The public plays little role in the above. It may be a big club, but the we ain’t in it — so cast your vote and hush. At least the recent relaxation of mail-in voting rules has made the former task easier:

But doesn’t the average American still control the public purse? Not really. 75% of the federal budget is already set aside for transfer payments and other mandatory spending. As for the discretionary budget, who has time for a 4000 page bill? There’s not much left for the ordinary citizen to do except watch the latest congressional investigation that will inevitably lead nowhere. Government is reduced to inept theater featuring a cast of bad-faith actors. Meanwhile, the juggernaut rolls along.

***

There’s nothing wrong with basing fiscal, monetary, or social policy on scientific evidence, assuming the data is freely evaluated and communicated. In fact, this is critical for social policy decisions. Yet why do these guidelines matter, and how does free speech tie in to all of this?

Suppose that a prevailing theory is wrong, yet nobody’s allowed to admit it. Instead of exploring alternatives, scientists are pressured to layer epicycle upon epicycle to make the model fit reality while journal articles fret over the mounting replication crisis. Increasing amounts of time, money, and energy become devoted to propping up a creaky construct.

And that’s just the academic world. Public officials seeking scientific guidance soon discover that expert recommendations don’t fix anything. Since the experts can’t be wrong, this merely proves — to the policy maker, at least— that the program needs more funding and better messaging.

When the policies still fail, it’s time to reflect. Surely, the fault can’t lie with the underlying model, so what — or who — is really responsible? That’s when the scapegoating begins: the citizens are to blame! As failures pile up, the government-media complex tightens the ratchet. A few more restrictions here, a little less free speech there. How else to nudge the public towards its moral duty? When the science is settled, skepticism becomes perverse.

Do any real world examples of this phenomenon exist?

Yes. For example, cognitive tests generally suggest a 15-point gap between Black and White IQ scores. Most scientists claim that this gap is completely environmental. This assertion is reasonable, and it’s not as if there is direct evidence for a genetic contribution at this date, but the pure environmental model makes predictions that it should satisfy if it’s valid. For example, if the environmentalist position is true, then early social interventions should be able to close this gap. And for young children, they do. Unfortunately, the gaps re-emerge by late adolescence, washing away most, if not all, of the gains.

This phenomenon is well-known. For example, in “Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments”, coauthors Richard E. Nisbett, Joshua Aronson, Clancy Blair, William Dickens, James Flynn, Diane F. Halpern, and Eric Turkheimer — all of whom endorse the environment-only hypothesis — are forced to concede:

The best prekindergarten programs for lower SES children have a substantial effect on IQ, but this typically fades by late elementary school, perhaps because the environments of the children do not remain enriched. There are two exceptions to the rule that prekindergarten programs have little effect on later IQ. Both are characterized by having placed children in average or above-average elementary schools following the prekindergarten interventions. Children in the Milwaukee Project (Garber, 1988) program had an average IQ 10 points higher than those of controls when they were adolescents. Children in the intensive Abecedarian prekindergarten program had IQs 4.5 points higher than those of controls when they were 21 years old (Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparling, & Miller- Johnson, 2002).3

[my emphases]

But what about those two exceptions? The esteemed researchers didn’t mention a few caveats about the Milwaukee Project. Like, for example, that the project might be a total fraud. As a well-sourced Wikipedia article mentions:

The Milwaukee Project's claimed success was celebrated in the popular media and by famous psychologists. However, later in the project Rick Heber, the principal investigator, was discharged from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and convicted and imprisoned for large-scale abuse of federal funding for private gain. Two of Heber's colleagues in the project were also convicted for similar abuses. The project's results were not published in any refereed scientific journals, and Heber did not respond to requests from colleagues for raw data and technical details of the study. Consequently, even the existence of the project as described by Heber has been called into question. Nevertheless, many college textbooks in psychology and education have uncritically reported the project's results.[3][4]

For those who reject Wikipedia out of hand, here’s an abstract from a peer-reviewed article:

Numerous methodological problems, such as questionable equivalence experimental and control groups, confusion over subject attrition and replacement, normative obsolescence of assessment devices, and inadequate independent IQ assessment, all cast doubt on the validity of the project's results. The failure of the principal investigator, Howard Garber, to respond to methodological criticisms and questions regarding the impact of Rick Heber's criminal activities on the integrity of the project data does nothing to quell the cloud of suspicion surrounding the research. The Milwaukee Project provides no support for the hypothesis that early intervention for children at risk for mental retardation will result in meaningful and lasting changes in IQ or achievement.

[my emphasis]

As for the Abecedarian project, a reduction of 4.5 points in the IQ gap is a good start, but a 4.5 point reduction still leaves 10.5 points on the table.

To be sure, these intervention programs have made a larger dent on other types of academic gaps, but as the authors admit:

The discrepancy between school achievement effects and IQ effects (after early elementary school) is sufficiently great to suggest to some that the achievement effects are produced more by attention, self-control, and perseverance gains than by intellectual gains per se (Heckman, 2011; Knudsen, Heckman, Cameron, & Shonkoff, 2006).

But is the racial IQ gap really 15 points? In a Vox article titled “Charles Murray is once again peddling junk science about race and IQ” that criticizes the Bell Curve coauthor, authors Eric Turkheimer, Kathryn Paige Harden, and Richard E. Nisbett assert:

The black-white IQ gap is decreasing, and is now closer to 10 points than the widely cited one standard deviation (15 points), which is the erroneous value Murray cites in the interview. Academic achievement of blacks has also improved by about one-third standard deviation in recent decades.

[my emphasis]

Where does the above bolded claim come from? They don’t say, but I have a pretty good idea. A famous peer-reviewed article by William Dickens and James Flynn compares the IQs of Blacks and Whites in various age groups, starting from 1972 and ending in 2002. They do claim that the IQ gap between Blacks and Whites is 9.5 points….for the age 12 test-takers. This backs up Turkheimer, Harden, and Nisbett’s claim that the gap is now “closer to ten points”. However, the very same paper then shows that the gap is 11.8 for the age 15 cohorts and 15.5 for the age 23 cohorts. Notice that the gap widens with increasing age, although the test-takers in each group admittedly come from different populations.

By comparing the IQ gaps in 1972 to 2002 at similar ages, Dickens and Flynn demonstrate that the gap narrows 5.5 points for each age group. However, it’s critical to note that Flynn and Dickens show that the adult IQ gap has shrunk from 21 to 15.5 points over the 1972 to 2002 time period, not from 15 to 9.5 points. So the current adult IQ gap is 15 points.

Now, let’s return to “Intelligence: New Findings and Theoretical Developments”. Recall that Nisbett and Turkheimer also helped coauthor this paper. What does the “Intelligence” article say about the Black-White IQ gap? Let’s see:

It is important to note that there is a dramatic decline of Black IQ with age. Four-year-old Blacks are only about 5 points below Whites of the same age, whereas at age 24, Blacks are 17 points below Whites. This could be, as it seems, a loss with age. But it could be that younger cohorts of Blacks (those born five years ago) have had more favorable life histories than older cohorts of Blacks (born 24 years ago). If it is an age effect, it could have either environmental causes (the Black environment becomes progressively worse and worse relative to the White environment) or genetic causes (genes dictate that Black cognitive growth with age is slower than that of Whites).

[my emphases]

Sure, that’s a possible environmental explanation for the widening gap. But what happened to Nisbett and Turkheimer’s confident claim in the Vice article that the “gap is now closer to 10 points”?

I suspect that the answer lies by looking at the other “Intelligence” paper coauthors, who are… William Dickens and James Flynn. I suspect that Nisbett and Turkheimer thought that they could get away with a tiny white lie when talking to Vice readers, but had to stick to the uglier truth when they were in the same room with the coauthors of the paper from which they had cribbed their misleading claim. Just a hypothesis, mind you.

What does this detour show? That focusing on only one explanation while scornfully dismissing other possibilities turns scientists into Janus-faced propagandists, publicly proclaiming that the dominant model is the only scientific one while privately conceding the model’s lack of explanatory power. But fear not, when it comes to environmental explanations, there are always new epicycles available when the old ones stop spinning.

As common sense suggests, every model is fallible and experts in the soft sciences can steer the ship off course as deftly as the rankest amateur. Immanuel Kant once said, “Aus so krummen Holze, als woraus der Mensch gemacht ist, kann nichts ganz Gerades gezimmert werden.”, which is elegantly rendered as “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” Anything built by humanity is by nature imperfect. However, imperfection can be diminished so long as the cycle of invention, correction, and refinement is lubricated by free inquiry.

So why hasn’t the internet reversed the public’s disengagement with civic life? After all, people can form international communities, access government documents, and consume fresh research with a few clicks of a mouse. Increased connectivity should have led to greater social harmony and government accountability.

It turns out, though, that virtual networks encourage people to nestle in algorithmic pods with news feeds tuned to the user’s biases. Without the moderating influence of face-to-face meetings at a fraternal order’s wood-paneled lodges, modern man is free to nurture secret grievances that echo and resonate in his digital cell. And he who bowls now, bowls alone.

The resulting online tribalism is no surprise. In the end, the only difference between the establishment and its detractors is the elegance of their respective cocoons.

Perhaps America is hopelessly divided and the average citizen destined for an atomized existence. However, only the freedom to speak one’s mind and question authority without the fear of cancellation can hope to revitalize democracy. Easier said than done, of course. However, the Elastic Clause of the Constitution provides a legal remedy to the media-corporate tyranny that besets us. Future essays will outline why I think bad ideas can be good and how the Blank Slate hypothesis has failed us all. I will also propose how we can extend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to ideological minorities.